| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

By Redlands Organic

Growers Inc

|

|

|

The no-dig technique is an old fashioned technique often promoted as the ‘lazy alternative’. It has many avid keen followers whilst other organic gardeners prefer the traditional methods of digging organic matter directly into the soil for long-term self sufficiency.

To create a successful organic garden, there are some elements you need to get right when developing the soil. In common with making a cake, miss out on one of the essential ingredients or use a substandard alternative and you will end up with a cake that tastes strange, is rock hard and/or is unappealing.

When preparing the soil, you need to think about the growing medium you will need – how are you going to amend the soil,

what you are going to use to improve it, how much is it going to cost and from where will you source the material?

All these questions are easily answered and this is where most people head straight for the local landscape supplier. However, quality of bought ingredients can vary greatly and in some cases substandard main ingredients can result in a poor productive vegetable garden.

Consider making your own soil amendments – it’s easy, light work, cost effective and most of all it’s fun! It is something that the kids will enjoy, your back will appreciate and you will be making the best growing medium that will turn out award winning produce.

The article also discusses: Making a Garden Bed – no-dig garden |

| |

| From

a 2 page Feature Article in Issue Twenty Three |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bitter Melon (Momordica charantia), also known as Bitter Gourd, Balsam Pear, Karella (India), Ku Gua (China), Peria (Malaysia), Kiuri (Japan) and Karawila (Sri Lanka), is very popular in Asia, but many Australians have never eaten it. Bitter fruits and vegetables are no longer widely eaten in the modern Australian diet, probably due to our growing addiction to sweet, sugary foods.

Bitter Melons are bitter – very bitter – but bitterness does vary among the many different varieties grown. It also varies depending on how the melons are prepared. In India the fruit is often boiled in salted water to reduce the bitterness,

before draining and being added to the prepared

dish or sauce.

So why would you eat such a bitter vegetable? Once you get over the bitterness – and after a few mouthfuls it does disappear – it has a very distinctive and addictive flavour. The fruit is used in soups, stews, stir fries, curries, pickles, omelettes and stuffed. You will find recipes for this fruit in many Asian cookbooks, particularly those focusing on traditional Chinese, Indian and Philippino recipes, and also on the internet. The author’s particular favourites are the Indian recipes where pre-cooked sliced fruit is added to spicy sauces. Young leaves and shoots are also eaten after brief cooking and you will often see them for sale in Asian markets.

Varieties noted briefly are:

- ‘Chinese Bitter Melon’

- ‘Warty Melon’

- ‘White Bitter Melon’

- ‘Small Bitter Melon’

Good to know…

If you are keen to grow a vegetable that is really healthy for you, this is it. Bitter Melon is renowned to be very healthy for you, being rich in quinine, and it is considered particularly beneficial for diabetics. Many people eat the fruit daily and attribute it to a long healthy life. In Asia it is taken medicinally to cure a number of ailments including summer colds, heat stroke, stomach ache, dysentery, conjunctivitis, boils and carbuncles. |

| |

| From

a 2 page Feature Article in Issue Twenty Three |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

SPECIAL

ONLINE CONTENT

The

below item complements this

article read in the current

issue:

Information on medicinal properties for garlic.

|

|

|

|

Garlic belongs to a large plant genus known as Allium and other more commonly known members of this family (Liliaceae/Amaryllidaceae) include onions, leeks, shallots, spring onions and chives, just to name a few.

These plants need full sun, excellent soil drainage and a slightly alkaline soil pH.

Elephant Garlic

Allium ampeloprasum

var. ampeloprasum

Elephant Garlic is not really true garlic but more closely related to the leek. The bulbs are huge and have a more subtle garlic flavour compared with other true garlic varieties. Elephant garlic grows from temperate to subtropical climate zones, which makes it an ideal choice for those warm humid climate zones that struggle to grow garlic successfully.

Elephant Garlic, also known as Russian Garlic, is native to Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia, Saudi Arabia, Israel, Turkey, United Kingdom, Bulgaria, Greece, Italy, France, Portugal and Spain. With such a spread of habitat it’s not surprising that this garlic is grown in a wide range of climatic zones.

Common Garlic

Allium sativum

It is thought that the garlic plant originated in Central Asia. Its popularity and use though, has been widespread for thousands of years. With evidence of its use dating back some 3000 years to ancient Greek, Egyptian and Indus civilisations, we can now find nearly every continent embracing this humble perennial bulb for its medicinal and

culinary properties. |

| |

| From

a 2 page Feature Article in Issue Twenty Three |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The common edible Fig (Ficus carica) a member of the Moraceae family, is a deciduous small tree producing its best fruit in the warm temperate and subtropical areas of Australia. The food value of the fruit, like that of the date, is increased with drying, making it a valuable source of nutrition.

Botanically, the Fig is a hollow, fleshy receptacle enclosing many tiny flowers. Figs are produced singly or in pairs and are classified by the colour of their skin – red, white, green, brown or black. The commonly grown ‘Brown Turkey’ is a vigorous upright tree producing a rich, sugary, white-green fleshed fruit, tinged with red at the centre.

Fig trees can survive temperatures of minus 10ºC when dormant, but need protection from late frosts which can damage the growing tips. They have a high requirement for calcium and therefore can tolerate alkaline soils, which must be well drained. During the first year in the ground they need plenty of water and fertiliser to be productive. However, too much nitrogen can cause excess leaf production and slow ripening of the fruit. Figs can be successfully grown in large pots. The restricted root system producing a smaller, more manageable fruiting tree.

Topics include:

- Pruning

- Propagation

- Fruiting

- Varieties

|

| |

| From

a 2 page Feature Article in Issue Twenty Three |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A recent trip to Thailand highlighted

the edible attributes of the genus

Tamarind, which many Australians think of as only an ornamental

street tree. The fruit is harvested as a commercial crop overseas where it is eaten raw or used as a delicacy for flavouring stir fries, curries, pastas and also as a component of condiments such as Worcestershire sauce.

Growing to 20 m tall in the wild, it may only reach 10 m in cultivation. It is slow growing and as such, mature specimens not only look stately, they take on the role as icons for homes, streets and also have cultural value, being featured in Indian scriptures written around 800BC as well as Buddhist writings from 650AD. |

| |

| From

a 2 page Feature Article in Issue Twenty Three |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

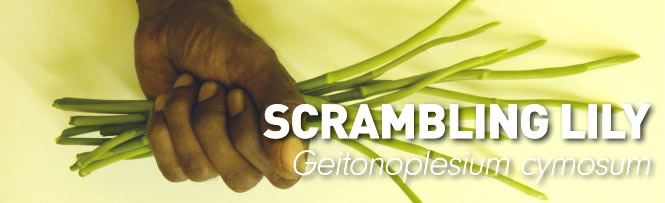

By the Queensland Bushfood Association

Images Graeme White and Mary King

Download the Bushfood Recipe as found on p.61 of STG Issue 23.

|

|

|

Aslender vine common on the margins of rainforests and the moister eucalypt forests of eastern Australia, from East Gippsland to north-east Queensland, it also occurs in Malesia, Melanesia and on a few Pacific Islands.

The Scrambling Lily is a wiry, twining climber and its growth habit is sometimes quite variable, making it hard to identify, as it is superficially similar to the Wombat Berry (Eustrephus latifolius), a close relative. The stiff, shiny leaves of the Scrambling Lily have a pronounced midrib only, whereas the Wombat Berry leaves have many raised longitudinal veins. Leaves are simple and alternate on zig-zag branchlets but give the appearance of being compound. |

| |

| From

a 2 page Feature Article in Issue Twenty Three |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| Ph/Fax

07 3294 8914 | PO Box 2232 Toowong QLD 4066 Australia |

| © 2005-2012 Subtropicalia Media Pty Ltd T/A Subtropical Gardening – All Rights Reserved

ABN 79 113 106 862 |

|

|

|